How investment bankers do it

When investment bankers advise companies on valuation, or when hedge fund analysts analyze companies to decide which ones to buy, they use “valuation multiples.” These are basically the same thing we did above.

There’s a term called “enterprise value”. This is different than the value of the company to shareholders or lender. Enterprise value is supposed to capture the value of the entirety of the company, independent of debt or equity.

Using earlier example, a lemonade stand that made $4,000 per year would be worth $50,000 if the corresponding rate of return is 8%. That is:

- $4,000 per year divided by 8% = $50,000

- Or, $50,000 times 8% per year = $4,000 per year

The $4,000 we’re using here means “cash flow”, or the amount of money we get to keep each year from owning the business. The $50,000 means the enterprise value of this business.

This means that someone who buys this business and is able to obtain $4,000 per year in cash flow from it, would be willing to pay $50,000.

If this business had $20,000 in debt, then that debt would typically need to get paid back first in case of a sale, meaning that there would be $30,000 left for shareholders. In this case, the enterprise value is $50,000, the debt is $20,000 and equity value is $30,000.

Even if the debt wasn’t repaid, and the buyer only wanted to buy the equity of the company (equity means stock or shares), the buyer would pay $50,000 minus $20,000 in debt = $30,000 to own 100% of the shares.

If the business had $10,000 in cash and no debt, a buyer of this company would be willing to pay an additional $10,000 for it, since it’s just cash. This means that instead of paying $50,000 for this business, the buyer should be willing to pay $50,000 + $10,000 = $60,000 for it.

Now, what if the company made $4,000 per year in cash flow, had risk that corresponds to a 8% required rate of return, $20,000 in debt and $10,000 in cash? What would the value to shareholders, or equity value, be then?

- The enterprise value would be $4,000 divided by 8% = $50,000

- Since we have debt, we subtract that from the $50,000, to end up with $30,000

- Because there’s cash in the company, we add $10,000, to get to $40,000

- So, the value to shareholders in this case is $40,000

In real life

We keep saying the company generates $4,000 in cash flow in the examples above. In real life, we use a term called “Free Cash Flow” or “EBITDA” to approximate “cash flow” for an enterprise.

EBITDA means earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. We won’t cover the exact meaning of this here, but we’ll touch on the interest part. For now, just now that it’s a term that’s used in reference to a figure that approximates “normalized cash flow”. The word “normalized” here means that it tries to do away with the various one-off ups and downs that occur each year, to get a number that’s more representative of what can be expected going forward in general.

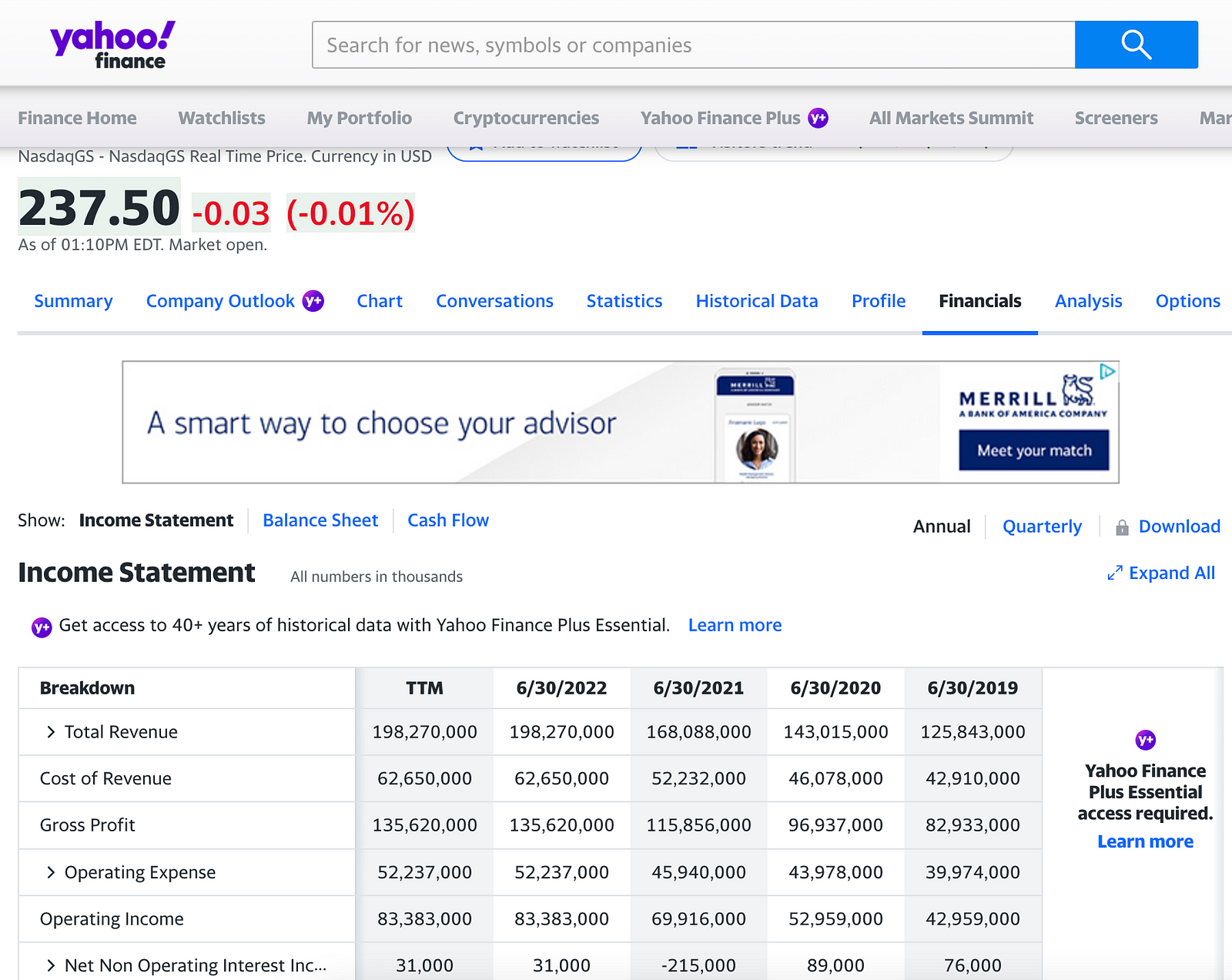

If you visit Yahoo! Finance and look up “MSFT” (the ticker symbol for Microsoft), you’ll be able to click on “Financials” to see their income statement:

If you scroll down, you’ll see a figure for EBITDA.

That figure (at the time of this writing) is $100 billion. Microsoft makes $100 billion per year that it can basically redistribute back to its investors. Of course, this statement isn’t entirely and there is more nuance to the real answer, but this is the general idea.

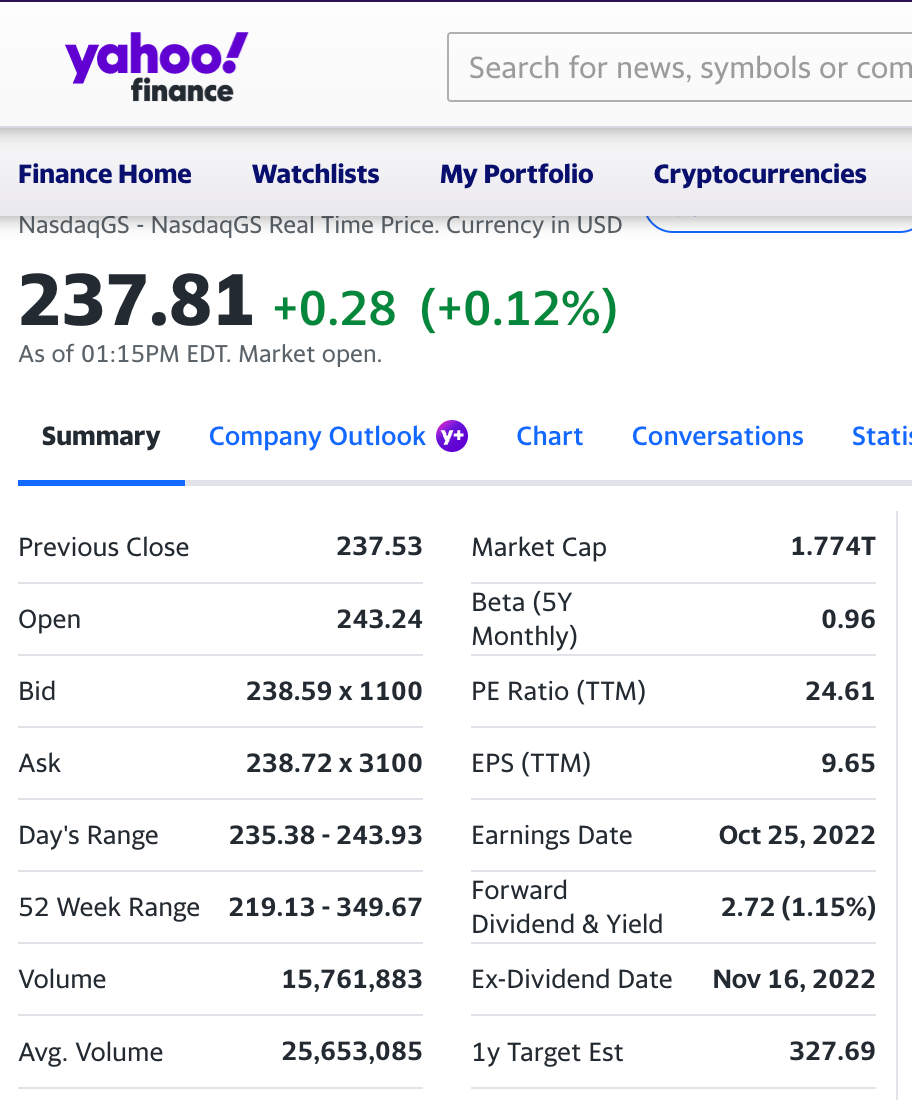

If we look at the summary page for MSFT on Yahoo! Finance we can see that it has a “market cap” of $1.774 trillion at the time of this writing:

“Market Cap” here means “value left over for shareholders”, or “equity value”, or “stock value”. If we divide this $1.774 trillion by the number of shares outstanding we get the share price, which is the “Previous Close” number of $237.53 above.

Remember when we said that Amigos Lemonade made $4,000 in profit each year and had 1,000 shares? The “profit per share” for Amigos Lemonade then was $4.00. This is the same thing as “EPS” above. “EPS” means earnings per share, which is the same thing as profit per share. Last year, Microsoft made $9.65 in profit for each share. So, if you bought a share for $237.53, that share would be tied to $9.65 in profit. Microsoft’s management and board can decide whether to take that profit and reinvest it for future growth, or to distribute it to shareholders as dividends.

The line that says “Forward Dividend & Yield” means how much Microsoft’s management and board is expected to give back to shareholders. Microsoft’s board can choose whatever number they believe is right at the time they announce the dividend. Looking back at history, investors can safely assume that Microsoft will issue a $2.72 dividend for each share. So, the profit per share here is $9.65, and of that amount, Microsoft will give $2.72 back to shareholders in the form of a dividend. The 1.15% in parenthesis just the divided of $2.72 divided by the price per share of $237.53 = 1.15%.

If you’re an investor in MSFT, you’re interested in how much MSFT could pay in dividends if they decided to give everything back to investors each year, as opposed to re-investing or accumulating cash. The number they’re interested is the “profit per share” or “earnings per share”, for the same reason we covered with our earlier examples with the lemonade stand.

So with MSFT we can buy a share for $237.53 and theoretically get $9.65 in earnings per share each year. If we go with the same logic we did in our lemonade example, this means that the rate of return we get from a MSFT share is $9.65 divided by $237.53 = 4.06% per year.

Do you see the PE Ratio of 24.61 in the Yahoo! chart above? That means “price to earnings ratio”. For MSFT, it’s just $237.37 divided by $9.65 = 24.61, which is the same thing as the reciprocal of what we did in the prior paragraph, or 1 divided by 4.06% = 24.61. They’re both the same thing. The reciprocal of the “rate of return per share” is the PE Ratio. The reciprocal of the PE Ratio is the “rate of return per share”.

But, remember in our Amigos Lemonade example, when grandma gave us a loan, we had to pay back that loan and interest before anything went back to shareholders? The same is true for Microsoft.

We can calculate Microsoft’s enterprise value by looking at it’s market cap, debt and cash, which you can find in the Yahoo! Finance page for Microsoft. I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to figure this out.

Using enterprise value, analysts will calculate metrics like enterprise value to EBITDA and enterprise value to revenue. EBITDA is an approximation to free cash flow, and you can think still think of it as the reciprocal in the examples above.